Logos. Pathos. Ethos.

During professional experience, I was amazed to see my Year 9 English class learning about definitions to these ancient Greek words within a module on advertising. Little did I know at the time that these three words comprised Aristotle’s seminal classification of rhetorical arguments (Corbett & Connors, 1999, p. 12).

Although steeped in ancient tradition, rhetoric should not be viewed as an antiquated preoccupation; the study of rhetoric is as relevant now as ever before (Hermann, 2018, pp. 44-49). Political speeches, social media and advertisements have found new and increasingly subtle ways to use rhetorical devices to influence and persuade (Villaneuva-Mansila, 2017, p. 113). With this in mind, if we want students to “read the world”, they first need to see how the world’s most influential ideas have been inflated and carried by clouds of hot air.

For essentially, rhetoric is the study of hot air; it traces how speakers command words to frame realities and to further their agendas, for better or worse (Bull, 2016, pp. 482-486). To empower critical thinking students who question dominant ideologies we must give students the power of differentiate between hot air and unequivocal truth (Charteris-Black, 2005, p. 126). For only by understanding how uncertain or fallacious arguments become gift-wrapped as truth can students unpack reality from, well, rhetoric.

Let me return to my opening line: logos, pathos and ethos. These three terms are easy to define and straight-forward to apply within the Stage 4 English classroom: i.e., there are 3 main types of arguments – logical arguments (logos), emotional arguments (pathos) and moral arguments (ethos); every persuasive text you respond to or compose is comprised of a combination of these 3 arguments (Leith & Myerson, 1989, pp. 87-89). This simple lesson opens students to a profound realisation at the heart of rhetoric: truth is an unstable concept; our realities are shaped by the arguments we find most persuasive (Cockcroft & Cockcroft, 1992, p. 58).

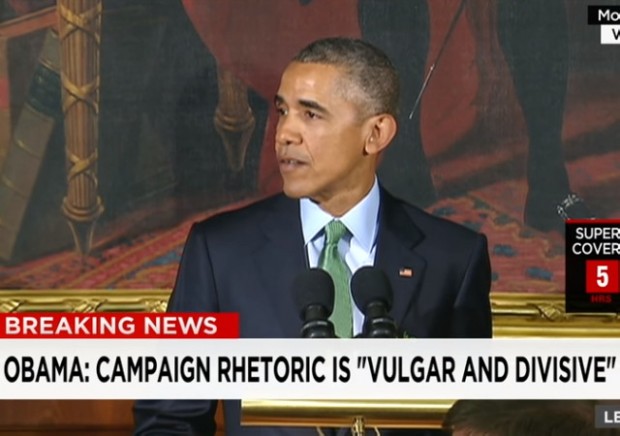

With the increasing use of ICT in classrooms, teachers can now show video and audio recordings of famous speeches throughout history to demonstrate the above insight. From Mandela to JFK to Gorbachev to Obama, there is a wide variety of political speeches that span cultures and contexts brimming with rhetorical devices for students to identify, explore, practise and finally master (Fengjie, 2016, p. 151). With multimodal texts a mandated component of NESA’s English syllabus, it is wasteful to merely present texts in class, prompt student analysis and later compositional work; without highlighting the rhetorical patterns that pervade famous speeches across generations (Olmsted, 2006, p. 7). Incorporating this historical dimension demonstrates how the word can literally change history while also staving off natural teenage self-centredness (Olmsted, 2006, p. 21). For while NESA’s increased emphasis on students’ personal engagement with texts is wonderful, this cannot be at the expense of students’ understanding of how their own compositions fit into the history of persuasive writing; treating each text as a silo of knowledge removes the greater significance of why we study English at all.

An obvious counterargument to rhetoric’s re-inclusion into the modern curriculum is that proficient teachers should already be facilitating performative tasks such as in-class debating to improve students’ speaking skills (of which rhetoric is one component). Having tried several in-class debating exercises at each of my professional experience placements, the issues with this perspective became clear: time constraints mean that the top-performing students (who usually have extra-curricular engagement with debating or public speaking) revel in the spotlight while less-advanced students either remain quiet or descend into inappropriate remarks. Without the frontloading of a rhetorical scaffold, speaking tasks only serve to reinforce students’ previously held beliefs about their English abilities: i.e., being good at English is further seen as a “natural gift”, a belief which motivates a few and demoralises most. Instead, rhetorical competency can demystify English and instil students with an increased self-efficacy that not only improves their persuasive writing but their competencies with other literacies too.

For example, Shakespeare’s texts remain an integral part of the English syllabus, a polarizing point that acts as the final straw in many students’ metaphorical relationship with literature. To remedy this, I’ve witnessed several teachers hide the written play entirely in favour of film and theatre adaptations. This follows the adage that Shakespeare is to be seen and heard, not read like a novel. Once students are hooked by a visually engaging adaptation, the study of Shakespeare’s use of rhetoric can act as a bridge that connects students back to the play’s literary devices, and by extension, the play’s deeper subtler levels of meaning that would otherwise remain unexposed. Framing questions from a rhetorical standpoint demands that students access higher-order thinking skills whether they want to or not! “Is Hamlet motivated by an emotional, logical or ethical agenda?”, “What rhetorical devices does Romeo use to woo Juliet?”, “What arguments does Iago employ to persuade Othello of Desdemona’s infidelity?”. The explicit teaching of rhetoric is an investment that leads to a deeper understanding of characters’ motivations and text-types’ differing purposes within Shakespeare’s plays and beyond.

For as the above example demonstrates, rhetoric’s value goes beyond students’ persuasive text responses: rhetoric highlights the musicality of language, improving students’ appreciation of poetry and prose as a positive by-product. Rhetoric also demonstrates the power of the spoken word, thus improving students’ critical literacy skills and giving students the necessary tools to both detect and then challenge inequalities for the purpose of social justice (McCabe, 2012, p. 41). Rhetoric’s place in the modern English curriculum should no longer be contested: how can we honestly expect students to write persuasively without first introducing them to the art of persuasion?

Hyperlinks to relevant media articles

Words actually can hurt, according to UCI researchers study of political rhetoric

A research study analyzes the concept of post-truth

References

Bull, P. (2016). Claps and Claptrap: : An analysis of how audiences respond to rhetorical devices in political speeches. 473-492.

Charteris-Black, J. (2005). Politicians and rhetoric : The persuasive power of metaphor / Jonathan Charteris-Black. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cockcroft, R., & Cockcroft, Susan M. (1992). Persuading people : An introduction to rhetoric / Robert Cockcroft and Susan M. Cockcroft.Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Corbett, E., & Connors, Robert J. (1999). Classical rhetoric for the modern student / Edward P.J. Corbett, Robert J. Connors. (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fengjie, L. (2016). Analysis of the Rhetorical Devices in Obama’s Public Speeches. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 4(4), 141-161.

Herman, R. (2018). Telling the Story and the Importance of Rhetorical Devices and Techniques. GPSolo, 35(5), 40-58.

Leith, D., & Myerson, George. (1989). The power of address : Explorations in rhetoric / Dick Leith, George Myerson. London ; New York: Routledge.

McCabe, K. (2012). Climate-change rhetoric: A study of the persuasive techniques of President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Julia Gillard. Australian Journal of Communication, 39(2), 35-57.

Olmsted, W. (2006). Rhetoric : An historical introduction / Wendy Olmsted. Malden, MA ; Oxford: Blackwell Pub.

Villanueva-Mansilla, E. (2017). Memes, menomes and LOLs: Expression and reiteration through digital rhetorical devices. MATRIZes, 11(2), 111-129.